|

Tandem Point(SM) Therapy:

An integrated acupressure approach for myofascial pain by Rena K. Margulis Presented to Rehabilitation Medicine Grand Rounds National Institutes of Health March 17, 2000 |

|

I would like to explore more deeply the reason why I think a muscle approach must be considered when a patient's films show disc degeneration. The clinician has the choice to view that evidence of degeneration in accordance with one of two models. Model A: Patient presents with pain. An X-ray or MRI shows a disc problem. The clinician can conclude that pressure on the nerve root is causing the pain. Here's a diagram of this model:

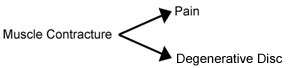

Clinical approach: NSAIDs, cortisone injection, sometimes surgery, "don't do what causes you pain." Yet Rene Caillet, M.D. wrote about a study of degenerative thoracic discs and pain: "Only 29% of asymptomatic patients had normal MRI scanning of the thoracic spine, whereas 60% of these asymptomatic patients were manifesting bulging or herniated thoracic disks with 54% showing evidence of spinal cord indenture, with 24% showing frank disk herniations, and with 46% having annual tears. These authors concluded that disk herniations are part of the normal aging process of the spine. Of symptomatic patients, 12% had normal results on MRI scan."(7) [Since this presentation, researchers at the Stanford University Medical Center reported on a study of "96 patients with known risk factors for disc degeneration. People whose discs had high intensity zones were only slightly more likely to experience back pain during normal activity than those without obvious disc problems. Additionally, high intensity zones were found in 25 percent of people who-despite their known degenerative disc disease-had no corresponding symptoms of low back pain." This research was presented April 12, 2000 at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine and earned the Volvo Corporation Award for the Clinical Study of Low Back Pain. It was to be published in the December 2000 issue of Spine.(8)] Such studies call into question the Model A practice of blaming pain on degenerative discs. Model B: Patient presents with pain. Regardless of whether an X-ray or MRI shows a disc problem, the clinician can search for a muscle contracture that could be causing the pain. From an X-ray or MRI, the clinician can visualize which muscles might be contracted to create a particular joint dysfunction. If releasing the muscle contracture eliminates the pain, consider the possibility that the muscle contracture was putting pressure on disc, leading to the degeneration. If the muscle contracture does not cross a vertebral joint, consider that the afflicted distal muscle may be affecting the segmental nerve, and the segmental nerve is contracting the muscles along the spine and other muscles innervated by that segmental nerve. This is the theory espoused by Chan Gunn, who writes: "Ordinarily, when several of the most painful shortened muscles in a region have been treated [with dry needling], pain is alleviated in that region. Relaxation and relief in one region often spreads to the entire segment, to the opposite side, and to paraspinal muscles. These observations suggest that needling has produced more than local changes-a reflex neural mechanism involving spinal modulatory system mechanisms, opioid, or non-opioid, may have been activated."(9) In short, distal muscle contracture may cause contracture of the paraspinal muscles, possibly leading to disc degeneration. I always apply Model B when a patient presents with pain and a diagnosis of a disc problem. I search for a muscle contracture that might be causing the pain, and usually I find it. If a muscle contracture leads to pain and disc degeneration, then the approach is to treat the muscle contracture. Here is a diagram of this model:

Approach: Treat the muscle contracture Omitted graphic: When muscles across a disc shorten, they compress it and at the same time, cause arthralgia in the facet joints. Source: Gunn CG: The Gunn Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain, Churchill Livingstone, New York, 1996, (p. 8). [Permission could not be obtained for reproduction of this graphic on a website.] Especially suspect muscle contracture involvement when stretching and/or massage improves the problem. If massage makes the problem worse, there also may be muscle contracture involvement, but the clinician may be massaging and releasing an antagonist which is splinting against the muscle in contracture. Case: Female, 61, a frequent recipient of Tandem Point therapy for assorted pain patterns. She presented on July 5, 1999 with pain on the lateral aspect of the left thigh and leg and pain in the posterior gluteal region. She reported that the pain began after hiking 10 miles in one day, and since had "come and gone on its own schedule." She identified the Travell & Simons pain referral pattern for the anterior division of the gluteus minimus as her pain pattern. Palpation found the anterior division of the gluteus minimus to be unusually hard. Tandem Point therapy was applied to the gluteus minimus trigger points plus Sp 6 and Sp 8, and immediately afterward the patient reported that her pain was gone. The patient then reported that the previously described pain pattern was the same pain pattern she had suffered before she had two back surgeries ten years earlier. Before those surgeries she had received no physical therapy, her physicians had not palpated her muscles, nor had they ordered an EMG to determine any muscle involvement. Follow-up: This patient received some further work on her gluteus minimus in two of her four sessions between July 5, 1999 and February, 2000. On February 14, 2000, she had no pain in the lateral aspect of her left thigh or leg.

|